Editor’s note: The following except on “Memory Aids” comes from Increasing Personal Efficiency (1925) by Donald A. Laird. Some re-formatting and condensation have been applied to the original chapter.

The strength of your memory depends upon the way in which you memorize rather than upon how much it is used. What you want to do is to learn the best ways of memorizing. After you have learned these, follow them rigorously until you have them ingrained as habitual ways of memorizing that you use without thought or effort.

Memory itself, probably, cannot be improved. We are limited by our natural gifts, but the ways in which we memorize can be improved. Therein lies the secret.

1. Be intentional in remembering.

The man who first said “it is the little things that count,” may have wanted to be funny, but he stated a truth of improving memory. The first “little thing” for you to correct is your intention in remembering.

Try to remember this phrase: intention has a lot to do with retention. Be sure to remember this because it is illustrative of one of the first steps in putting memory on a serviceable basis.

When one tries to remember, his memory works much better than when it is left to drift for itself. It has been found that, when one tries to remember, he does remember 20 percent better for a few hours. This same little effort improves memory for longer periods of time by as much as 60 percent.

Apply this every time you run across something that may be useful. When you are introduced to a person say to yourself: “I must try to remember him”; you will remember him much better. When you chance upon a bargain in the advertisements say: “I must remember this” and you will save your pennies, and the embarrassment of forgetfulness.

It is not fair to complain of a poor memory until you have really tried to use what you have in the best way. The ability to remember is there. It is up to you to make the most of it.

2. Memorize the new through the old.

Can you recall the shape of Italy?

Can you recall as accurately the shape of Germany?

You can remember the shape of Italy much better because, when you studied about Italy, its shape was nothing new. It was merely an old-fashioned boot. When you learned this, you had nothing new to remember. What you did was to connect the new notion of the shape of the country with an old idea already in your head.

The secret of your better memory in this case is that you had memorized the new through the old. This is a very important memory aid to use continually.

When was the Chicago World’s Fair? You probably cannot recall. I am going to show you how to connect this new with the old so that you can remember this date easily. This fair was to celebrate the four hundredth anniversary of the discovery of America. Of course you know that America was discovered in 1492. That is an old memory. For hundred years later make the Chicago fair in 1892 but, because the buildings were delayed a year, the actual year of the fair was 1893.

Isn’t that much easier than repeating 1893 over and over again? It is not only easier; it makes a more lasting memory. And it is not only more lasting. Doesn’t it mean much more to you now than it would have if you had merely used brute force and memorized 1893 as the date without having the new memories connected with the old ones?

Do you know the German word for dog? It is hund. This can be easily remembered by connecting the new with the old in this way: Hund is much like hound, and hound is an old memory of yours. With one stroke such as this, you have a memory of a foreign word that will last some time.

Not every new thing can be so easily connected with old memories. The point for you to follow, however, is to look for any associations you can possibly find. Do not memorize things as being entirely new; refresh your old memories until you run across some connecting link. You will thus make the new easier to remember, and you will also have strengthened your old memories by reviewing them.

How can you remember this memory aid by connecting it with the others we have given?

When and why was the Chicago World’s Fair?

3. Cultivate a broad range of interests.

At the circus, you saw many people who were strangers to you. Of all these, which ones would you recognize if you were to see them again? Probably the fat woman and the human skeleton.

Let the fat woman teach you something about improving your memory. She was remembered when hundreds were forgotten because you gave her more attention than you did the normal-sized persons. She was unusual and interesting. This caused you to fix your attention upon her and a more vivid impression was made than if she had gained only casual and passing attention.

What did you read in yesterday’s paper? You can probably remember only the items that attracted your attention. That is why most readers remember the novelties of the news rather than the more significant events. You will notice, too, that the advertisements you remember were the large ones or the unusual ones.

The unusual house or the loud automobile is remembered better because they arouse our interest. The interesting public speaker is remembered because interest holds attention, and attention increases the vividness of our memories. Interest and the attention it brings makes otherwise ordinary things vivid. The person who has many and strong interests remembers better than the ones with only a few weak ones.

You probably have trouble remembering names because you are embarrassed when introduced and give attention to complexion and clothes rather than to the name. Hereafter whenever you make a new acquaintance invariably make it a special point to remember their name and their face.

Test your interests in this way: what can you remember from the daily paper? Is it mostly sport news? If so, it is because your interests lie there. Is it the theatrical news? If so, there are your interests too. Or is it the really worthwhile things you remember?

Improve your memory by cultivating an interest in everything you read or hear. Maintain this interest through life, and add further to the vividness of your memories by giving attention only to one thing at a time, and by going slowly until you can feel that a vivid impression has been made. Haste makes waste and not vividness.

One vivid impression is remembered better than three ordinary impressions.

4. Talk over the things you want to remember.

Do you reinforce your memory? When you want to remember some facts, do you just look at them or do you repeat the figures? Do you write them down and think about them for a while? If you look at them and think: “How interesting, I must remember this,” you are improving your memory by this added effort. But you will not have reinforced it.

Reinforce your memories of the news of the day by talking over what you have read at the table. Reinforce your memories of the best markets by talking over the advertisements. Reinforce your memories of the movies you see by talking about them from time to time.

A student of mine recently performed some experiments which revealed that one remembers 15 percent more a week after memorizing things that are heard as well as seen. This is a very simple way for anyone to improve his memory by merely talking over what he has read or heard. Not only will this aid your memory efficiency but it will give you something about which to talk and perhaps change you from a conversational bore into an interesting person to have around.

Among my friends is a physician who is superintendent of a hospital with twelve hundred patients. This a great accomplishment in itself. More important from the psychologist’s point of view is the fact that he has a tenacious memory for names.

He reinforced and improved his memory for names by getting each name through his eyes, his ears, his mental pictures, and by writing it. After he had become adept in this, he never forgot a name memorized.

When you are introduced to a stranger and want to remember the name do not just say “how ‘de’ you.” Repeat his name as often as possible. Disregard etiquette and say: “Glad to know you, Jones.” Repeating the name as well as hearing it reinforces your memory.

If you have been in the habit of laboriously writing down things you want to remember, you are reinforcing your memories slightly, but stronger memories have been found to result from repeating and talking over the things to be remembered. Try this out yourself by talking over the significant news of the day, then think the same news over tomorrow and you will be surprised how great an improvement you have made.

5. Revive your recent memories.

Here is an easy test for you to try on your memory: What did you read about in the last section? Can you remember the section before that, and the one before that? If you go back over your reading, in memory, you will note that you have great difficulty in remembering what you have read even six hours ago. It is but little harder to remember what you read six hours ago than it is what you read two weeks ago.

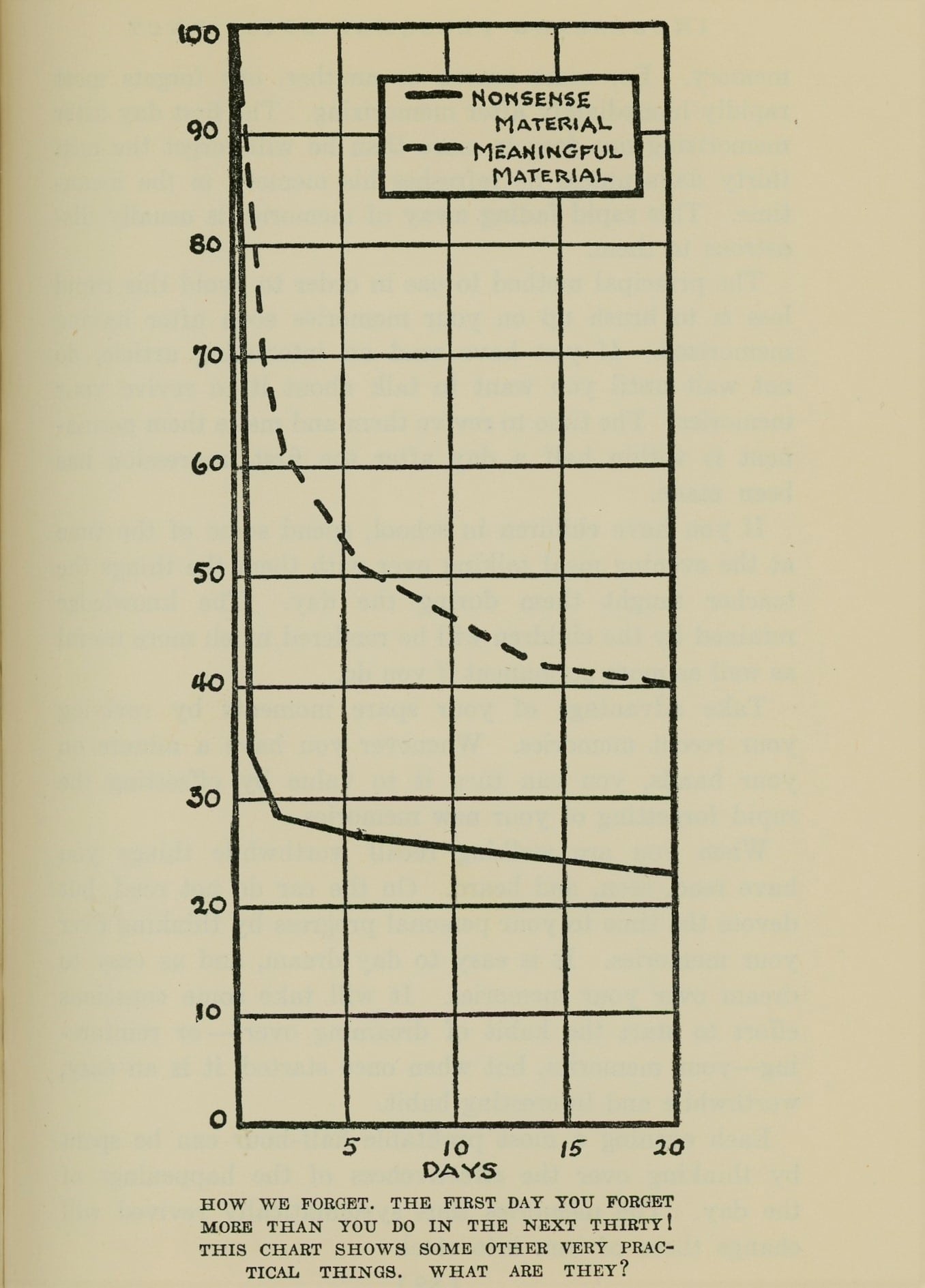

This illustrates an important and very practical law of memory. For some reason or another, one forgets most rapidly immediately after memorizing. The first day after memorizing one forgets more than he will forget the next thirty days unless he refreshes his memory in the meantime. This rapid fading away of memories is usually disastrous to them.

The principal method to use in order to avoid this rapid loss is to brush up on your memories soon after having memorized. If you have read an interesting article, do not wait until you want to talk about it to revive your memories. The time to revive them and make them permanent is within half a day after the first impression has been made.

If you have children in school, spend some of the time at the evening meal talking over with them the things the teacher taught them during the day. The knowledge retained by the children will be rendered much more useful as well as more permanent if you do.

Take advantage of your spare moments by reviving your recent memories. Whenever you have a minute on your hands, you can turn it to value by offsetting the rapid forgetting of your new memories.

When you are walking recall worthwhile things you have read, seen, and heard. On the car do not read, but devote the time to your personal progress by thinking over your memories. It is easy to day dream, and as easy to dream over your memories. It will take some conscious effort to start the habit of dreaming over – or reinforcing – your memories, but when once started, it is an easy, worthwhile, and interesting habit.

Each evening a most profitable half-hour can be spent by thinking over the effectiveness of the happenings of the day. The memories thus systematically revived will change those of iron into steel.

6. Repeat what you want to remember.

Would you like to have your memories one and a half times as strong as they are now? You can improve them by this amount if you repeat everything you want to remember twice.

How would you like to have your memories twice as strong as they are now? You can more than double their strength if you repeat what you want to remember three times.

Repetition, which is the old stand-by in improving memory, thus is found to be of considerable value, even though there may be diminishing returns. Repetition alone, however, is not the most desirable memory aid. One should understand thoroughly what he is to remember before it is repeated. The layman can memorize difficult medical terms by repeating them alone, but is the memory worth anything if it is not thoroughly understood?

Do not entertain the notion that it is childish to repeat the things you should remember. If you want strong memories you must repeat them. Do not think that your memory is weak if it will not retain things when you read them or mention them only once. You must strengthen your memories by repeating the material you want to remember well. That is the way you memorized the multiplication table, which is probably one of the strongest memories.

When you are introduced repeat the name several times by saying, “Glad to know you, Mr. Jones. We were just talking about the tariff, Mr. Jones.” Thus you have repeated the name twice. Jones feels complimented when you mention him by name, and your memories are strengthened every time you do.

If you care to have all your memories as strong as our memory of “two times two equals four,” use repetition freely.

7. Memorize meanings.

Your sense will improve your memory and your memory in turn will improve your sense, if you go about it in the right way.

One who does not understand the language of finance has a sorry time remembering when he reads the market pages. Likewise, if he is not well versed in sports, a description of a game in the sporting section is scarcely remembered. This is because he does not understand and sense these particular subjects.

A few days ago I was with a group of chemists. The day after, my friend and I talked over the conversation. I remembered but little of it while scarcely a phrase had faded from his memory. I could not remember it because I had not understood what they were talking about. My friend, the chemist, had remembered it because the conversation had made sense for him.

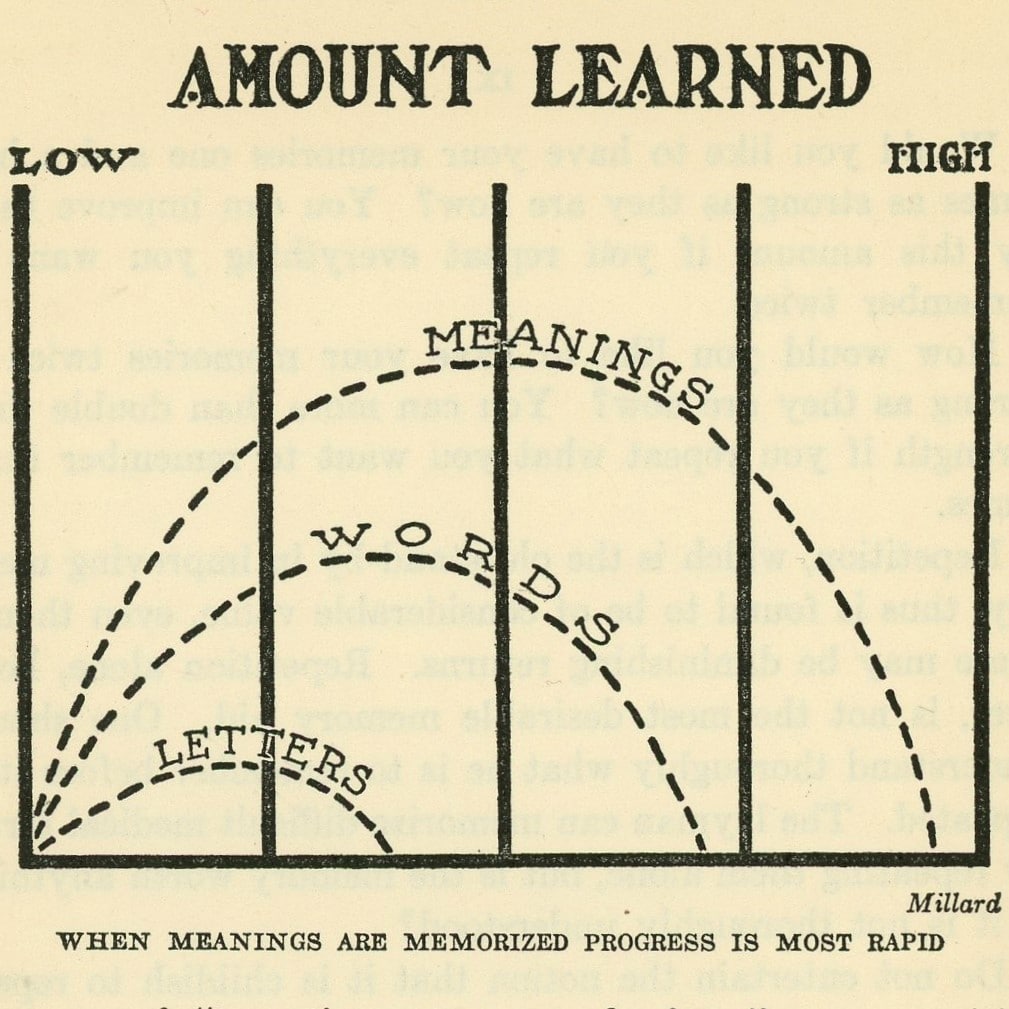

Give your memory an additional lift by memorizing meanings. Can you remember this: Use sense to improve your memory? Can you remember this: Sense memory to your use improve? You remember one because it has sense for you. The other has the same words but is many times harder to remember because there is no meaning that you can attach to it.

You can remember quicker when you look for the meaning; you will also remember longer when you have memorized the sense. Use the dictionary to help you get clear meanings. If the sense is not clear to you, study over the word or phrase until you understand it. Read your papers and magazines for meanings rather than for words. Look for the meaning in conversations and speeches. You cannot possibly remember all the words of the minister, but you can easily remember the sense of his talk.

Put this into practice now by turning to the editorials and reading one for its meaning. It will put more sense into your head and the sense will make it easier to remember. Try for the next few days to develop the habit of reading for the meanings. Neglect the words for they are important only insofar as they give the meaning.

8. Memorize early in the day.

When does your memory fail you most, in the morning or in the evening? Can you memorize as quickly in the afternoon as in the forenoon?

Last year I experimented with 112 of my students so that I might answer these questions. The experiments lasted six weeks and required almost five thousand tests.

I found that one can memorize for ideas best in the forenoon. It is about 5 percent less efficient to memorize in the afternoon, and about 6 percent less efficient to memorize in the evening. From eight until ten in the morning was found to be the best period to memorize for those who arise at seven.

It is probably easiest to memorize in the forenoon because fatigue is least then, and because there are fewer new impressions in the nervous system.

Sunday seems to be the worst day of the week to use one’s memory. This is probably because we take things so easily on that day that our mental machinery is not warmed up and working at its best. Early morning memorizing, immediately after rising, is not effective because the mental machinery, as it were, is not warmed up.

If you are doing some serious study, why not rise an hour earlier than usual, exercise a bit to get warmed up, and study then rather than in the evening when efficiency in memory is 6 percent lower?

Remember that your retentive powers lose in strength gradually from waking to retiring, so do your serious memory work accordingly.

9. Approach memorization with a positive attitude.

Do you dread memorizing? When you have a name to remember, do you dislike memorizing it? When you have a speech or some shopping items to remember, are you bothered by the fear that you will forget them?

This attitude really makes memorizing harder, and increases your chances of forgetting the very things you want to remember. Your attitude has much to do with your mental efficiency.

At the University of California, it has been found that one’s mental efficiency is improved when he makes believe that the work he is busy at is fun and not hard. The work itself, of course, cannot be changed, but the efficiency of the mental life in going at the work is greatly increased by making a pleasant approach to it.

You no doubt have seen some one of your acquaintances stand with his heels to the corner and bend over to touch his forefingers at the level of his knees. Now this can be done easily so long as he does not think it is unusually hard or an impossible stunt, but just as soon as there is a crowd around insisting that it is a hard stunt and that it is impossible for him, he finds himself unable to do it. His attitude has made an easy stunt impossible.

It is much the same with memorizing. The child who thinks that the piece he has to learn for Sunday school is hard, will take twice as long to memorize it as he would if he thought it easy. So with your memory; things will be remembered easier and longer if you look upon using your memory as fun rather than as drudgery. No child should be brought up to think that mental work is hard or irksome, and any adult who feels that way should speedily change his attitude.

If you cannot actually and genuinely change your inner attitude, merely “faking” an attitude of pleasure will be of help. Try assuming this attitude that assists your efficiency the first time you note the “drudgery” attitude creeping over you.

After you have fallen into the habit of looking upon memory and all mental work as being great sport, you are likely to find that it is fast becoming a real and permanent attitude. It should.

Why not pretend that work and memorizing and thought are fun?

10. Make “overmemorizing” a habit.

Students especially, and all of us to a great extent, seem to think that too much memorizing is bad. In consequence we find the student studying his lessons just barely enough to be able to remember them the following day, and we find the salesman remembering the name of his new customers only a day or two.

Much forgetting is due to the fact that we seem to seek the easiest way and memorize only enough to remember for a few hours or days. Never stop memorizing as soon as you can repeat the name, or date, or information accurately. Spend some additional time memorizing it even after it is apparently well learned.

What can you recall of the Civil War history you were taught in the grades? Probably but little because, at the time, you were, like the rest, studying just barely enough to be able to remember the lesson for the recitation on the following day. Much education is wasted in this way. Education should be a life-long acquisition, but unfortunately it fades rapidly. This is because students are not taught the value of too much memorizing.

Information that is memorized well enough to be remembered tomorrow will not be remembered a week later unless it is overmemorized or other precautions are taken to keep it from fading. After you can remember what you are reading or studying, memorize it a little more. It is this additional memorizing that will make the memory permanent.

The physician who has his information in his head is the one who overmemorized in college; the one who has to consult his books again and again is the one who memorized just enough to get by in his examinations. The engineer who has to use the pocket manual continually is the one who failed to overmemorize.

You can remember certain things you have read in this book today. If you want to remember these tomorrow and make them a part of your permanent information, review them at once and overmemorize them.

Make overmemorizing a habit; it is a “factor of safety.”

No comments:

Post a Comment